I’m An Influencer. Why Do You Hate Me?

by Marissa Pomerance

Hi. My name is Marissa. And I’m the managing editor of this site. I’ve written about my anxiety and hypochondria and years of TMJ pain. I’ve done deep dives into endometriosis and estrogen and raged about zoodles and straight legged jeans.

But there’s something I haven’t written about yet.

Before I started here at The Candidly, I moonlighted as an influencer. Ok, more than moonlighted. It was my job.

I was an influencer.

It’s easier now to frame it as a “side-hustle” or temporary gig because the word itself is so inflammatory. And I’m hesitant to admit I was a full-time influencer when I’m afraid everybody will hate me for it. I’m afraid you’ll hate me for it.

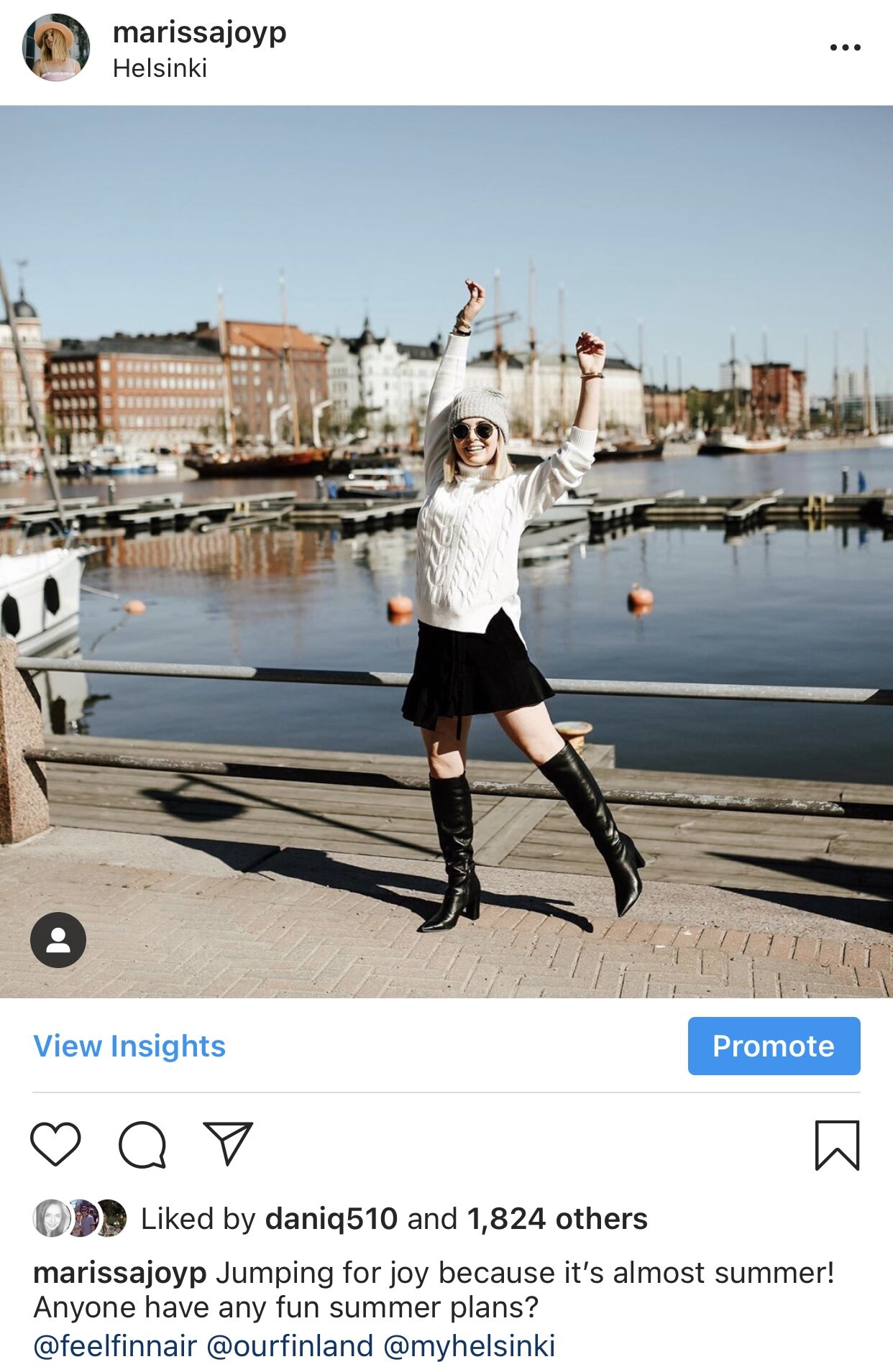

I’m afraid you’ll hate me for my wanderlust-y travel photos, like this:

Or my very blatant, paid ads, like this:

Or just those good ole’ selfies, like this:

But I’m curious. Why do you hate me?

Though I’m pretty sure I already know the answer.

I’m pretty sure there are 6 reasons why you think you hate me. But 2 reasons why you actually do.

1. You Hate Me Because It’s Trendy

All one has to do is search “influencer” on Buzzfeed for proof. Buzzfeed’s M.O. is creating the juiciest headlines that will garner the most clicks possible. They are truly masters at this. They know what sells, and they know that “Influencer Getting Called Out On Instagram For Being An Asshole” works every time.

The media industry has a vested interest in discrediting influencers. According to James Nord, founder of Fohr, one of the first influencer marketing platforms in the world, a lot of this influencer hate was originally generated by embittered editors working for dying magazines. “These people who were making hundreds of thousands of dollars working at magazines saw their careers going away. And these young kids-- that aren’t great writers, that don’t have journalistic training-- are just publishing on the internet. And of course you’d be bitter and pissed off, that’s totally natural. But they held that power so they had the ability to write those articles bashing influencers.”

But, he argues, “it wasn’t influencers that took magazines down,” says James. “It was the democratization of content that did.”

2. You Hate Me Because Being In The Public Eye Means I’m “Asking For It”

Did this influencer deserve death threats because she posted a staged photo on Instagram? Like, does she deserve to die for doing this? You, a sane person, is saying “no, that’s unadulterated insanity,” and thinking those are probably fringe lunatics sending her death threats. But having anyone threaten to kill you, even if they’re a fringe lunatic, is an utterly traumatic experience that no one should have to endure, especially because of an Instagram photo.

Because by that logic, any actor who complains about the paparazzi stalking them, are also “asking” for it by being famous, and so should Kirsten Bell and Jennifer Garner and Halle Berry and Christina Applegate just not have kids because their fame is “asking” to be hounded every second of their lives by aggressive paps with flash bulbs? Please tell me you’re with me on this. You’re with me on this, right?

3. You Hate Me Because I Don’t “Do” Anything

Ok. Now we’re really getting into it.

Maybe you just hate influencers because you don’t think they do anything of value.

Define “value” for me, first.

Look, I won’t pretend every photo I’ve ever posted to Instagram was a stroke of genius. In fact, most of them were not. But I can tell you this—creating content is a job. And just growing a following on social media is itself a full-time job— if you don’t believe me, just Google it.

But most people are completely unaware of the work it takes to grow an engaged audience, which is where some of these misperceptions about “value” come in. “Everyone has published an Instagram photo,” says James. “So it’s this really unique job because it’s making money off of a thing that most other people do every day. That feels really unfair. Because they think the job is posting to Instagram. The job is building the audience. That is incredibly difficult to do. People think, ‘oh, so you make $5000 on an Instagram post that takes you 5 minutes?’ Well yeah it does, but it took them 10 years to build the audience.”

And usually, the influencers who make the most money are actually the influencers who, in fact, create the most value. “Part of being an influencer should mean that you have some level of knowledge and expertise that you can teach people things,” says James. “They have a point of view that’s unique. At the end of the day, money talks. When an influencer puts her collection up and it sells out immediately, then yeah, she’s influential—she sold something and created something of value.”

Look, you still might not think this should be a real job, and you still might think that none of this has any value. And you’re welcome to that opinion. But honestly, your opinion isn’t really relevant. As James puts it, “if you’re a marketer that still believes that influencers don’t matter, then you. Are. Wrong. This industry is a ball of inertia. The ship has sailed. The world has changed. The influencer space is growing. And people being pissed off that it’s growing isn’t going to stop it from growing. Rage against the dying of the light all you want, but it’s changed. You want to stomp your feet? Cool. It’s irrelevant.”

But let’s assume for a second that you only hate those specific influencers who don’t work hard or produce anything of “value.” But don’t those people exist in every other job and facet of the world?

James equates this to other industries. “Daniel Day-Lewis and Rob Schneider are both actors,” he says. “But they don’t do the same thing at all. If you watched a Rob Schneider movie and said, ‘this is complete fucking trash, actors are terrible,’ you’re doing a disservice to what it means to do that job.”

And even if you hate Rob Schneider movies, ask yourself this-- do you actively hate Rob Schneider himself, or do you just decide to not watch his movies, scoff when you see the trailers, and move on with your day?

Posing in front of beautiful vistas is probably what you think I do all day, right?

4. You Hate Me Because You Think I’m Perpetuating A Culture Of Over-Consumption

Over-consumption is a real concern— I agree. I’m an advocate for slow fashion and eco-friendly products and a considered, mindful approach to purchasing. I’ve even RAGED against the trend machine.

But some influencers? They buy into this culture as much as the next person. They post “haul videos.” They promote the newest, greatest product that we all need to go out and buy NOW. Yet, there’s a reason why these “haul videos” get so many views. And why advertisers spend gobs of money on influencer marketing.

People like buying things.

So influencers are only a symptom of our culture of over-consumption, not the cause. Is it fair, then, to HATE them for it? Influencers may make a living off of promoting products, but they are just ONE outlet for products and brands and ads.

Do you also actively, vehemently, vocally "hate" all TV stations that run ads all day long? Do you "hate" magazines that fill their pages with ads? Do you “hate” every ad-riddled website? Do you "hate" all commercials? Do you "hate" any brand that pays for advertising? Do you "hate" every celebrity who endorses products?

“do you “hate” Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, who promotes his tequila and branded gear and sleeveless hoodies? ”

Do you “hate” beloved celebrity, Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, who promotes his tequila and branded gear and sleeveless hoodies on Instagram? Are you personally blaming him for our consumerist culture?

My guess? Probably not.

And while we’re on the topic—what are you, personally, doing about this culture of greed and overconsumption? Are you advocating for minimalism? Are you actively seeking out environmentally-friendly products? Promoting mindful purchasing practices? Providing tips and guidelines on how to be a more responsible consumer?

Because influencers like Lauren Singer, Shira Gill, and Kathryn Kellogg are.

So do you actually “hate” influencers because of “overconsumption,” or is that just a made-up reason to justify your truer, deeper feelings?

5. You Hate Me Because You Think I’m Entitled

Ah, yes. One of those empty words du jour that we use to mean “this person annoys me.” Someone’s an asshole? Entitled. Flaunting their wealth? Entitled. Asking for free product? Another level of entitlement.

People who ask, nay, demand free product must be entitled. I mean, brands can’t just willingly supply people with free stuff in exchange for something as silly and meaningless as social media coverage, right?

Actually, they do. Happily.

In fact, for many brands, sending out free product is a strategic business decision that leads to lucrative sales. “Let’s look at some of the consumer brands in the last year or two that have ticked over into billion dollars companies. Kylie Cosmetics. Away Luggage. Glossier. All of those were influencer-first brands. Influencer marketing made those brands,” says James.

Brands and influencers work together well. It’s a symbiotic relationship that, for the most part, works out for both parties. Whether you like it or not, influencer marketing is effective.

Of course, like in any business, not all of these relationships pan out. In fact, brands politely declined my collaboration requests all the time, and I turned down brand requests daily.

Yet the last few years has produced a trend of calling out influencers who reach out about collaborations. Like this blogger who asked for a free stay at a hotel in exchange for social media coverage— except, she was publicly vilified for it.

A free stay at a hotel in exchange for a few measly photos on social media? Am I kidding?!

I’m not. This is actually quite normal.

“Let’s say you’re a hotel, and I say, ‘I’ve got a stadium down the street which is filled with 100,000 travel fans. In the middle of that stadium is a person that they all respect and admire and listen to, and they’re going to talk about your hotel for 5 minutes, and you’ve got to comp a room for two nights to do that.’ There’s literally not a person in the world that would say no to that,” says James. It’s an exchange of services that benefits both parties.

And sure, some of these businesses are too small to support giving out free product or free hotel stays. So if brands can’t accommodate influencers, or aren’t interested in social media coverage, then guess what?

They can just say no.

Businesses like that aforementioned hotel can (and often do!) politely decline and explain that they don’t do these kinds of collaborations. Or they can ignore the request—they’re not required to respond! Just like any other business proposal.

So why call out an influencer who reaches out about a pretty standard social media collaboration?

Ironically, because of the power of social media.

By publicly calling out an influencer for requesting free stuff, a brand can simultaneously play into the public’s need to hate influencers while reaping the social media rewards. It’s smart marketing, really. They know their story will get picked up by other media and shared. Brands have built entire followings off of hating influencers, helping to boost their own business and sales from followers and supporters that share in their anti-influencer vision. So while they are simultaneously decrying the uselessness of social media influencers, they’re actually proving their value by demonstrating the power of an effective social media campaign.

James has seen this happen time and time again. “This goes viral twice a year—that a brand burns an influencer. But I don’t pay much attention to it because the world has already changed.”

And if you’re still unconvinced because you don’t think influencers should be accepting free product or trips or ad money in the first place, well, that’s a valid point. But free product and press trips are actually pretty standard in media. More importantly though, influencers have never claimed to be non-biased sources of information, like Consumer Reports. They’re individuals, not brands, and we follow them for that reason. We follow them because we want to know which jeans that curvy fashion influencer prefers, or what meal this food influencer is making for her family after work. We want to know what women like us think and feel and do.

And if you don’t, then you…don’t have to follow them.

6. You Hate Me Because You Think All Influencers Are Only White, Thin, And Rich

Which—in and of themselves aren’t great reasons to hate someone. Coupled with other things, sure. White and racist? Please go to hell. Promoting unhealthy body image? Feel free to hate. Rich and greedy/snobby/out of touch? They’re trash. But…just white, rich, and thin? Not great standalone reasons to hate someone.

Also, it’s…not true.

“Social media is a mirror,” says James. “The people saying all influencers are just white, thin, and rich are probably just following a bunch of white people. But that is an America problem. Is that because white people aren’t actively seeking out influencers of color and only following people that look like them? Yes. Is that because of the standards of what we consider ‘beauty’ have traditionally excluded non-white communities? Yes. But influencers aren’t creating that. In fact, if you look at the last $10 million that we’ve paid out to influencers, 65% of it has gone to non-white influencers. In the last 2 or 3 months, over 50% of dollars have gone to black influencers,” says James.

In reality, social media has perhaps given more visibility to traditionally marginalized voices. According to James, “one of the reasons that beauty Youtubers specifically blew up was because the content used to be controlled by the big magazines. They would do a beauty tutorial in their magazine, and it was always with a white girl. Because those stories weren’t being told, because the powers-that-be were all white, beauty influencers started translating those looks for different backgrounds and ethnicities. So it was really ignoring those communities that created the influencer space.”

And POC influencers have provided those much-needed spaces for connection for their communities. “I absolutely LOVE that everyone can find an influencer that looks like them, wears their size, shares their values, or has the same taste,” explains Brittany Hennessy, co-founder of influencer education company Carbon August, and literal writer of the book, Influencer. “You don’t need to wait for mainstream influencers to know what’s happening in your niche or the problems facing your demographic, you can be that voice, create that content, and connect with those brands.”

It’s the hard work of POC influencers that have pushed so many industries forward. Would makeup brands have started launching 40-60 inclusive foundation shades had it not been for black beauty bloggers shining a light on the lack of products that were made for them? Would traditional media outlets have been pushed to re-evaluate their business practices had it not been for POC employees with influential followings?

So influencers are actively challenging those traditional standards of beauty. According to Brittany, “at first, influencer marketing followed the same trends as advertising/acting/modeling in that they all promoted a specific type of aspirational beauty. But as more people joined social media and saw they could build communities for people who looked like them or had similar lifestyles we saw a shift.”

7. But Here’s The Real Reason You Hate Me

We’ve finally arrived here. To the elephant in the room. The real reason people hate influencers. After years of personal experience, I can tell you that it comes down to this.

Influencers receive a special kind of hate and resentment that harbors a deep, rumbling undercurrent of sexism.

But you’re probably a woman. And you’re probably a feminist. But we’re all guilty of saying ugly, petty things about other women, so let’s stop pretending that this has nothing to do with us. If we want women to stop being publicly shamed for existing, we need to take stock of our own biases while dismantling the patriarchy.

“influencers receive a special kind of hate and resentment that harbors a deep, rumbling undercurrent of sexism.”

Also, let’s be real-- this is an industry filled with women.

“There’s definitely some sexism. I think about why aren’t influencers more celebrated in advertising? This is largely a women’s world. Most of the influencers we work with are women. 98% of my clients are women. And 78% of my company is women. Most of the CMO’s of the world are men. Most of the marketing directors of the world are men,” says James.

Which probably explains this pay disparity between male and female influencers. Women make up 77% of the influencer market, yet men are still paid more:

How often are men even characterized as “influencers?” Almost never. They’re “photographers,” “content creators,” “Youtube stars.” “Influencer” basically means “woman.” According to Brittany, “when people say ‘influencer’ and mean it in a derogatory way, they usually mean fashion, beauty, and lifestyle influencers. You don’t really hear these things about comedy influencers, gaming influencers, sports influencers, finance influencers, or cigar/whiskey influencers, which tend to be male dominated industries.”

So when someone says they hate influencers, they’re saying they hate women. Yes yes, “not all women,” I know. Just ones who post pretty photos to Instagram. Or have a following. Or take selfies. Or make Youtube videos. Or post photos of themselves in bikinis. Or post photos of their stretch marks. Or were on reality shows. Or are married to someone famous. Or have a line of cookware at Target. You know, those few, specific women.

And sure, we hate Logan Paul. But we don’t hate him only for being an influencer, we hate him because he’s an asshole.

But people don’t hate influencers for simply being women. They hate them, specifically, for being women who represent all of the things they hate about women.

Influencers make a living by openly discussing topics typically dismissed by society as “superficial” or “stupid.” Ever notice how things that are stereotypically women’s interests, like beauty or fashion, are considered frivolous, and therefore constantly trivialized? Women have been told for centuries that our self-worth depends on our appearance, yet if we show any interest in our appearance, we’re dismissed as vain and narcissistic.

Men, shockingly, don’t seem to suffer from this Catch-22. Sports? Important! Economy-stimulating! A vehicle for the greatest, most talented human beings on the planet! Fashion? Useless. Consumerist. Made for jejune morons who just want pretty things that cost obscene amounts of money. It’s simple; if women’s interests are not valued, then women who make a living through those interests are perceived as less valuable members of society.

And to make matters worse, influencers are unapologetic about their interests. Gasp!

They produce girly, pink-filtered mirror-selfies and they don’t accompany any of this with a disclaimer. They take photos with their “girl squad” and they don’t care if you think their interests are frivolous.

And importantly, they don’t pretend to be the “cool girl.”

Instead, influencers shamelessly promote their femininity. They use their looks to their advantage, playing into the male gaze, reclaiming it, and monetizing it. And that blatant femininity—that promotion of female interests without caveat or comment or apology—seems to, well, tweak the fuck out of people.

While influencers can represent idealized versions of femininity, their public personas also conflict with the complicated, twisted ideas of how we want women to act; women must be quiet and obedient, but strong. Beautiful but not know it or act upon it. Stick thin with boobs but not work too hard for it (or dare consider plastic surgery). Wear make-up but never too much or too little. Dress well but not care about dressing well. She must portray the exact right brand of feminism, or she’s not a real feminist, or she’s not a feminist at all, or she’s too feminist. And she must balance it all easily and never complain and still look put together but not flaunt it or make anyone else feel bad.

No woman can be everything, so we always fall short. And who better to both represent and flout these impossible standards than women who publicly parade their lives on social media? Influencers are easy, public targets to direct our frustrations; we can pick them apart for not meeting our insane expectations, or for representing those insane expectations in the first place. Either way, they, we, can’t win.

But along with sexism, there’s another deep, insidious reason for hating influencers that most of us would rather shove away to some corner of our soul than ever admit to…

8. Envy.

These people make us feel bad about ourselves and our lives.

So we hate them.

Just casually dancing on a helipad. Like one does.

They represent something that while we might not overtly want, we also know we’ll never achieve. And we know social media is a fake, filtered, photo-album version of someone’s life. But when those are the images we’re bombarded with on a daily basis, it becomes harder to separate those filtered images from the expectations of ourselves and our lives.

That influencer galavanting on a yacht in the Maldives while we’re working 12-hour days from a job which will never pay us enough for a yacht and coming home to screeching children and unappreciative husbands invokes nothing but pure envy. Must be nice to not have a real job. And a working mom whose Instagram makes everything look so easy, like she can juggle all of it, or afford nannies and day care and a giant house with plenty of room? Must be nice to have a rich husband.

According to Celeste Grant, social media expert and founder of social media consultancy, Zing Social Media, “there is definitely a level of jealousy that can be thrown on to an influencer. They get all the ‘free stuff’ for seemingly doing ‘nothing.’ However, if you know anything about content creation, you know it’s not easy work.”

Of course, these impossible standards of perfection can be a serious issue, especially in the broader context around social media. The teen suicide rate has increased, which experts attribute to the increased use of social media platforms. What people post to these platforms matter, and the messages espoused by influencers can have broad consequences, especially if they’re contributing to the idealization of false forms of perfection.

And while the exact causal role between social media and suicide isn’t firmly established, it’s easy to see how social media could simply be a louder, more direct tool for bullies to taunt and embarrass, and make the already heinous pubescent experience even more comparative, lonely, and divisive than it already is.

These conversations about regulating social media, weeding out bullies and negativity, and using platforms to promote more positive messages around beauty and mental health are deeply important and necessary. But, is it fair to hate all influencers for this shitty system? Wouldn’t our anger be more effective if directed elsewhere, like at the platforms themselves and the failure of our mental healthcare systems that allow half of all children with mental health issues in this rich, prosperous country to go untreated?

Shouldn’t we be treating the cause, not the symptoms?

“but influencers give us a convenient, delicious scapegoat to point the finger.”

But influencers give us a convenient, delicious scapegoat to point the finger. To distill and direct our anger at social media, cyberbullies, and the state of the world. We’re mad because their privilege represents growing income inequality. We’re mad because they have a platform to spew their uninformed opinions. We’re mad because they don’t seem to follow the same kinds of rules that us regular folks do. Even if we know that none of these things are, systemically, their fault.

But.

How do you explain away the Kardashians?

They are, in essence, the original influencers, and now, the most extreme version of “influencer.” And they represent the perfect distillation of this hatred—we see them as the pinnacle of vapid failure. They embody our loathing for a world where ignorance is revered and excess is encouraged.

But they are still a scapegoat for all of our deepest darkest feelings about who among us deserves to have 9 fridges in their house. And that certainly can’t be someone who makes culturally-appropriated shapewear and cries when she loses a diamond earring. She has children for heavens’ sake. We don’t believe they deserve their wealth and privilege. So? We hate them for it.

And when we hate people, we are usually just sitting in judgement. And the essence of judgement is self-protection. That filtered, shimmering Instagram feed has the immense power to make us question ourselves. So we find a cozy, safe place to deposit those feelings of insecurity, and channel them into proving that influencers are vapid. And fake. And worthless.

But isn’t it on us to try and understand the source of our own feelings and judgement? To have enough sense of self that our identities can’t be easily threatened by a photograph of a stranger?

Because here’s a hard truth. Influencers aren’t going away.

As long as social media exists, they’ll be there. And if we want to figure this out—“this” meaning social media and pretty girls taking selfies and the veiled sexism that goes along with hating those pretty girls — we’re going to have to do it together.

Don’t believe this kind of aggressive, abusive, vitriolic hatred of influencers exists? Keep scrolling. The comments below sum it up nicely.

Marissa Pomerance is the Managing Editor of The Candidly. She’s a Los Angeles native and lover of all things food, style, beauty, and wellness. You can find more of her articles here.