How To Be Less Defensive

by Marissa Pomerance

“You really can’t take feedback.”

I’ve heard this many, many times. And I just want to yell, “yes I can!”

Cutely ironic, yes?

Even while writing this article, I’m sort of dreading the part when I turn it into my very fastidious editor (hi Audie!) to receive her notes, and have to try to accept them graciously instead of feeling totally dejected and defeated and explain to her all the reasons why she’s wrong (she’s probably not wrong) and why it’s fine the way it is (it’s not), and why I already have plenty of grounded examples (I don’t).

I’ve always struggled to accept criticism. About myself. About my work. Mostly about myself.

“Feedback” cuts me to my core. Hearing that I’m “not detail-oriented” and that I “let little mistakes slip through the cracks” at work makes me question my intelligence. Hearing that my sloppiness is “inconsiderate” makes me feel like a selfish partner/roommate/sister/friend/daughter. All of it makes me feel extreme guilt and shame.

I am constantly working on my defensiveness. Constantly. But it wasn’t until I discovered this one new way of thinking about it that I actually made any progress. And here it is:

I have to learn to be OK with feeling bad.

Defensiveness is not the same thing as strength.

Before we really get into it, let’s unpack this a little bit more. Because like many of you, I’ve often equated “defensiveness” with “strength.”

We’re told that standing up for ourselves is good. We shouldn’t take any else’s shit! Especially in this Instagram-therapy environment, we’re supposed to point the finger at all the other “toxic” people who are the REAL problem.

And yes, standing up for ourselves, especially as women, is important, and a good skill to work on…but at a certain point, it becomes counter-productive, stunts our growth as humans, and makes interconnectivity 100x harder. Like when we say things like:

See?! It actually WASN’T my fault that I forgot to order you the things you needed on Amazon because I told YOU to remind me, and YOU forgot to remind me. So really, this one’s on you.

OR, when we forget a family member’s birthday and say:

It’s really not that big of a deal, and clearly you don’t understand how much pressure I’m under. I can’t believe you are trying to make me feel bad about this when you know how hard I work, and you’ve probably forgotten my birthday before, too.

Often, when we think we’re setting a boundary, or refusing to be a “doormat,” what we’re actually doing is protecting ourselves. We don’t want to hear critique, so we form an argument to prove it’s not true.

I’m a master at this. I gather my evidence. Make my case. Argue until I win. Once you get the hang of it, it becomes second nature to distort and manipulate words to suit the picture you’re painting of complete innocence. It’s probably not surprising that I’ve been told my whole life that I’d make a great lawyer. Except, now I’m not a lawyer, so my argumentative nature is less “impressive,” and more “grating.”

Because defensiveness is not strength. It’s a shield we hide behind. It’s also a tether to versions of ourselves that no longer serve us.

Real strength is vulnerability. Taking responsibility. Being able to admit when we made a mistake. God, that’s gross.

Actually, defensiveness is a coping mechanism.

So why do we do this? Well, it’s a coping mechanism. Defensiveness convinces us that we’re right, so we don’t have to take responsibility for the things we’ve done wrong, which allows us to pass the hot potato of shame and guilt that we fear will otherwise burn us. Smart!

“Defensiveness is used as a way for us to distract ourselves from our feelings of pain or hurt,” says relatable women’s therapist Amanda White. “Feeling as though someone is disappointed in you, frustrated or wants you to change your behavior can be difficult to sit with and it’s even harder to take ownership of your mistakes.”

And like most coping mechanisms, it’s one that we probably developed in childhood. According to White, “if as a child, you don’t learn healthy communication or conflict skills, you are more likely to adopt defensiveness as a coping skill. This is common if your family didn’t model healthy communication skills, whether they were defensive themselves, gave each other the silent treatment, were passive aggressive, or brushed things under the rug.”

For most of us, this is all tied up in our self-esteem and perfectionist tendencies, especially “if your caregivers correlated your worth based on performance,” White says. “As a result, if every time you didn’t perform well your caregivers were harsh or denied you of love and care, it makes sense that a child would become defensive in attempts to protect themselves.”

Like most coping mechanisms, there comes a time when it stops being necessary for survival, and starts being detrimental to our overall well-being.

For me, this only becomes truer the older I get.

Image from @thisisyolandarenteria/ Instagram

Ok, get to the fucking thing already.

I just made you slog through 2.5 Word doc-length pages so we can all fully understand that we act out in defensiveness because we feel bad.

And the “magic” trick for becoming better, less-defensive humans is learning to sit with feeling bad.

Ugh.

But HOW?

I know. Not easy. In fact, very scary and I truly wouldn’t blame you if you clicked out of this article right now. I would probably do the same thing.

Human beings aren’t good at sitting with discomfort—in fact, our discomfort with discomfort is at the core of many coping mechanisms and anxious behaviors.

But learning to recognize, acknowledge, and sit with bad feelings that we usually don’t allow ourselves to feel is the first step to becoming less defensive. This requires accepting that we are not perfect. That we are humans who make mistakes.

And that that doesn’t mean we have no worth.

Here’s how I (imperfectly) practice this:

1. Notice: “When you feel an emotion, rather than distracting yourself, numbing it or trying to stuff it down, practice being curious about it and witnessing the physical sensation in your body and the thoughts that arise. Many of us do not have this skill and need to increase our ability to sit in discomfort. It gets easier over time,” recommends White. When I’m acting defensive, I’ll try to recognize what I’m feeling and why. For example, “I’m feeling defensive because I made a mistake, and it’s making me feel like a worthless idiot.” And then I give myself a few minutes to sit with those feelings. I try to see how it feels to not pass that hot potato—sometimes, it’ll actually start to feel…OK. Even bearably lukewarm.

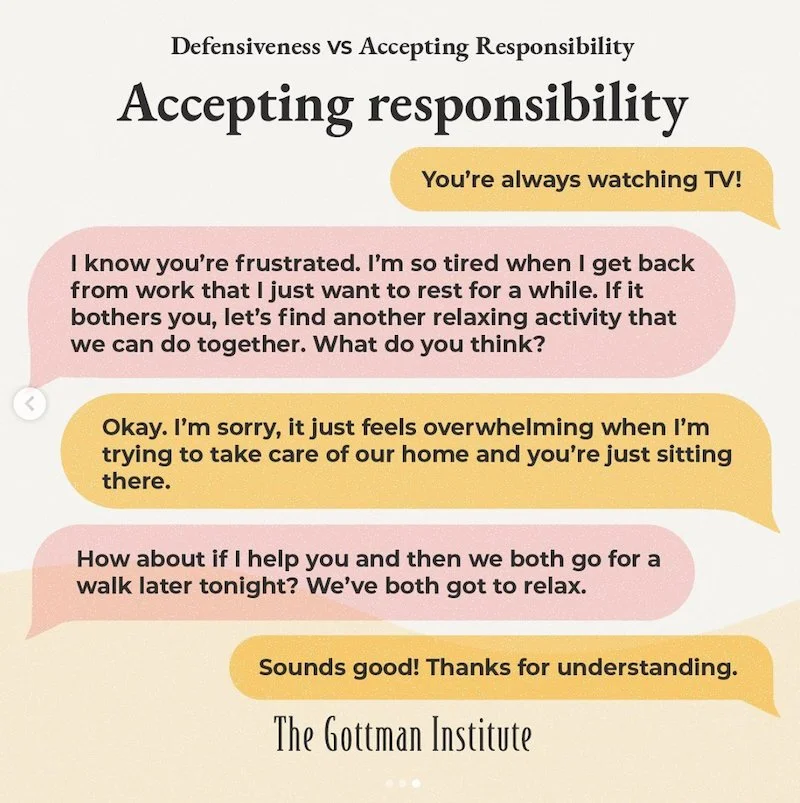

2. Take responsibility: And then I’ll, deep breath, try to…ugh…take responsibility for what I may have done wrong. God that was so fucking hard to say. But once you have the noticing and accepting and sitting with your feelings down, the natural next step is to practice the action of not being defensive, which means saying things like, “I’m sorry” and “I was wrong” while not breaking out into full body hives. So now, those examples from earlier might look like:

You’re right. I’m sorry. I forgot to order you those things you asked for on Amazon. I know I can be forgetful, and I’m going to set a reminder for myself next time to make sure it doesn’t happen.

And:

I’m sorry. I really messed up and forgot your birthday. I want you to know I care about you and value our relationship. How can I make this up to you?

See? I like that person better already. And when we lead with honesty and vulnerability, not defensiveness, we’re usually met with more kindness and understanding in return.

3. Work on self-esteem: Now, those are a few in-the-moment solutions. But the longer-term solution requires not allowing feedback to annihilate our self-esteem. And for most of us, this might be a process of untangling our delicate sense of self-esteem from the things we feel shittiest about (aka: I should not be building my self-esteem around being “detailed-oriented” or “good at cleaning”). According to White, part of cultivating self-esteem is practicing self-compassion: “With self-compassion, we recognize that humans are imperfect and make mistakes. You can remind yourself that it is understandable to feel defensive or angry if someone is giving you difficult feedback. Talk to yourself like you would talk to a loved one.”

Like I said-- none of this is easy. These are all muscles that we build over time with practice.

But eventually, we’ll become stronger. In fact, we might even become the strongest versions of ourselves yet.

Marissa Pomerance is the Managing Editor of The Candidly. She’s a Los Angeles native and lover of all things food, style, beauty, and wellness. You can find more of her articles here.