How To Not Ruin Your Child

by Audie Metcalf

First of all, I can almost guarantee that I’m ruining my child as I type this, so please know that I’m not an expert in anything. Truly. I haven’t even officially logged my required 10,000 hours of parenting to become Malcom Gladwell-certified.

So if I’m not an expert, why write this?

Good question. And here’s the answer.

Something I am slowly but steadily becoming an expert on, is myself. My reactions, my triggers, my huge gaps in my ability to connect, my lack of empathy, and my sad truth that most of my basic emotional needs were not met as a child. And through that painful process, I have stumbled on some universal truths about what human beings need in order to feel safe and seen and alive. And by “stumbled on” I mean “spent thousands of dollars on therapy to figure out how the fuck to be a good parent.”

“i have stumbled on some universal truths around what human beings need in order to feel safe and seen and alive.”

What is exhibited to us as children by our own parents, sets up a complex wiring system in our brains — a nuanced collection of data and responses that creates our emotional world as adults, complete with an extremely sophisticated set of tools for self-protection, especially when we didn’t receive a lot of the requirements small human beings need to become healthy, functioning, self-aware adults.

Many of these ideas are the cornerstones of NARM, or NeuroAffective Relational Model, a method of psychotherapy that, frankly, needs a swift rebrand, because the name sucks, it barely has any practitioners, and its “intro” book is essentially a flake-dry medical journal. But it’s also the most modern, holistic, thoughtful approach to healing and understanding developmental trauma, with the goal of helping people become well-adapted, fully formed adults. So. Ya know. Good with the bad.

Let’s get into it.

1. ATTUNEMENT

In plain words, this is what every human being wants on planet earth. And it’s at the core of being a not-bad parent. And honestly, it might also be at the core of being a not-bad person.

Essentially, attunement is being aware of, and responsive to, another person. It’s all the stuff that is very hard to control in yourself, but which makes a massive difference in the “felt” relationships of the people around you. And its importance is critically felt in our children. Having attunement with our kids helps them to feel seen, safe, and secure, which in turn creates a more secure “attachment” to us, and therefore the child is comfortable being themselves, and sharing themselves with others.

Finding attunement with our own kids, especially when we didn’t have attuned parents, can feel close to impossible. But there are two key ideas to consider:

Actually listen to their needs and feelings. This can be frustrating because they will shriek, scream, tantrum, yell, and whine their needs sometimes. The magic response is just to listen, and to repeat back to them what they said.

Really hear their point of view. This one can be tough. Their point of view can be so outside the scope of anything you understand and connect with sometimes, and it’s so easy to try and course correct them into our own narratives. But don’t. Just listen to it. If their point of view is that they want to be a professional basketball player when they grow up even though they have shockingly poor hand/eye coordination, it’s fine. They just want to know that you hear and support them.

2. MIRRORING

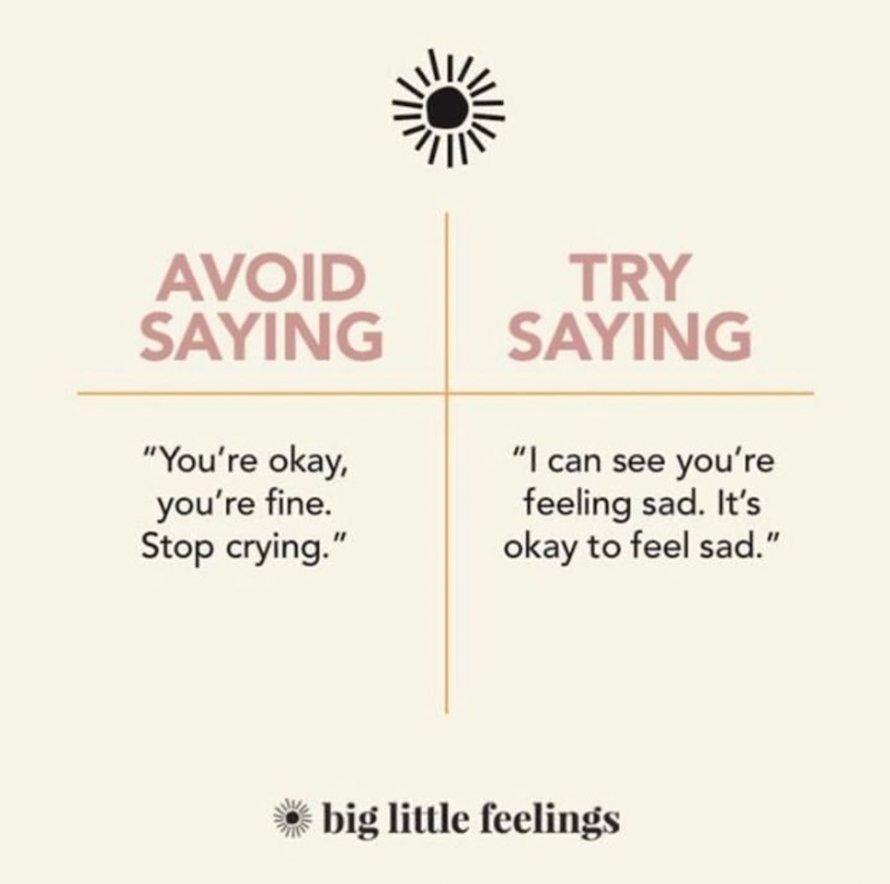

Mirroring and attunement are sort of sisters, but mirroring specific needs and feelings back to your child is a form of validation, validating that their existence and experience matters, and is something that opens the door to their own ability to have and show empathy. Without these moments of mirroring and empathy, your kid is forced to negotiate either preserving the “attachment relationship” (their bond to you) or their own feelings. And because kids are designed to protect the “attachment relationship” this means they push their own needs and feelings to the side. A phrase often used in NARM is “what’s disallowed is disavowed” meaning, when a kid has a feeling, and there is no empathy or validation for that feeling, the kid is forced to put that feeling somewhere else (disallowed), and judge it harshly (disavowed). If it’s not valid to the parents, and our entire job as kids is to protect our relationship with our parents, well then that feeling must be disgusting, weak, worthless. Which is what eventually becomes our inner monologue.

Here’s an example:

Kid: “ I JUST REALLY WANTED THAT OTHER PINK TOOTHPASTE I HAD AND YOU GOT ME THIS WHITE TOOTHPASTE THAT ISN’T PINK AND I HATE IT!!!!!!!!”

Parent: (without mirroring): “That toothpaste is ORGANIC and comes in a pack of THREE ON AMAZON and I’m not going to sit here and debate with you, it’s time for bed, enough with the whining about COLORS OF TOOTHPASTE this is RIDICULOUS.”

Parent: (with mirroring): “Are you so upset right now because you expected it to be pink but it’s white?”

Yes. It can supremely hard to stay in your present, adult self in these moments. And this article isn’t really about “how to deal with tantrums.” Rather, it’s about seeing your child as a totally separate person, with a rich inner life, full of emotions and feelings that are completely valid and real. Even though those feelings are about the color of toothpaste, which is just so so so easy to dismiss in the moment. But when their perspective is heard, and repeated back to them, especially in moments of them experiencing breakdowns, it is shocking to watch what happens next.

“when their perspective is heard, and repeated back to them, it is shocking to watch what happens next.”

…which is that they usually calm down, almost immediately. They have been heard, they have been validated, they got what they needed.

My knee-jerk impulse is to railroad their feelings on toothpaste color, but only because it was railroaded for me when I was a child, so it’s all I know. But all I knew was lack of attunement and mirroring. I have to really remember these steps as an adult now, and it doesn’t come naturally yet, but this is what rebuilding our emotional reactions looks like. It’s hard. As fuck.

3. CURIOSITY

This word seems like an obvious word. You know it and you use it. But it is not an obvious word. It is a magic word.

This word is most revelatory when you are neck-deep in a whining, weeping, cajoling, begging, howling, stomping scenario with your child, because so much of why that behavior occurs is because this small creature, who has almost no agency, has to be dragged to Costco with you, and go to bed exactly when you tell them, and eat whatever is on their plate. So for me, instead of being reactive when they whine about those things, I try to bring curiosity. And please know that I am not trying to be some sanctimonious shithead here. This is hard for me. It’s why I’m writing this. I’m sure there are people for whom this is natural and not hard. And I bet those people had really attuned, mirroring, curious parents.

So, in those moments when they don’t want to eat their broccolini even though broccolini is their self-proclaimed “favorite green thing” but are now describing it as “too tree-y,” instead of telling them to clean their plate otherwise there will be no dessert/TV/playtime/insert whatever stick-based consequence here, what if you were…curious about why it’s too tree-y? Maybe she’s over broccolini and it’s time to introduce her to the deeply underrated bok choy. Maybe she’s in the middle of some kind of brain/taste development and she’s now experiencing broccolini’s flavor in a new way. Maybe you over-fucking-cooked the broccolini. Where there is curiosity, there is the power to see things differently, and to engage, not just react, from our fully adult selves.

Since learning about curiosity, I feel like I have a super power. Curiosity feels like the antidote to judgment. Curiosity has led to me having more choices. And having more choices feels like the biggest secret to experiencing a better life that no one tells you about.

I waited until the end of this article to tell you that the person who has made me a mother is not my biological child. She is my stepdaughter.

I’m not sure why I didn’t lead with that.

Maybe because I thought my perspective would be seen as less powerful. It’s possible I’m projecting, and those are just my own insecurities getting in the way, but it’s also possible that you would have taken all of these ideas less to heart because I’m not a “real” mother. It would certainly have been a cleaner ending to omit this information, because projecting or not, discipline, reactivity, and whether any boundaries exist for stepparents, is a very murky place. If they aren’t really “ours” do we have all of the same rights, and the same rights to have all of the same feelings, as “real” parents?

Writing this entire article was a hard choice, to be honest. The subtext is: I’m not naturally good at this. That’s really hard to say. I’m the Editor-in-chief of the very site you’re reading, and internally we talk a lot about how we want to share things people don’t usually discuss publicly, especially about the always complicated, often lonely subject of parenting. I ask our writers to reveal incredibly personal things about motherhood and identity, as evidenced here, here, and here. And it only seemed right that I do the same.

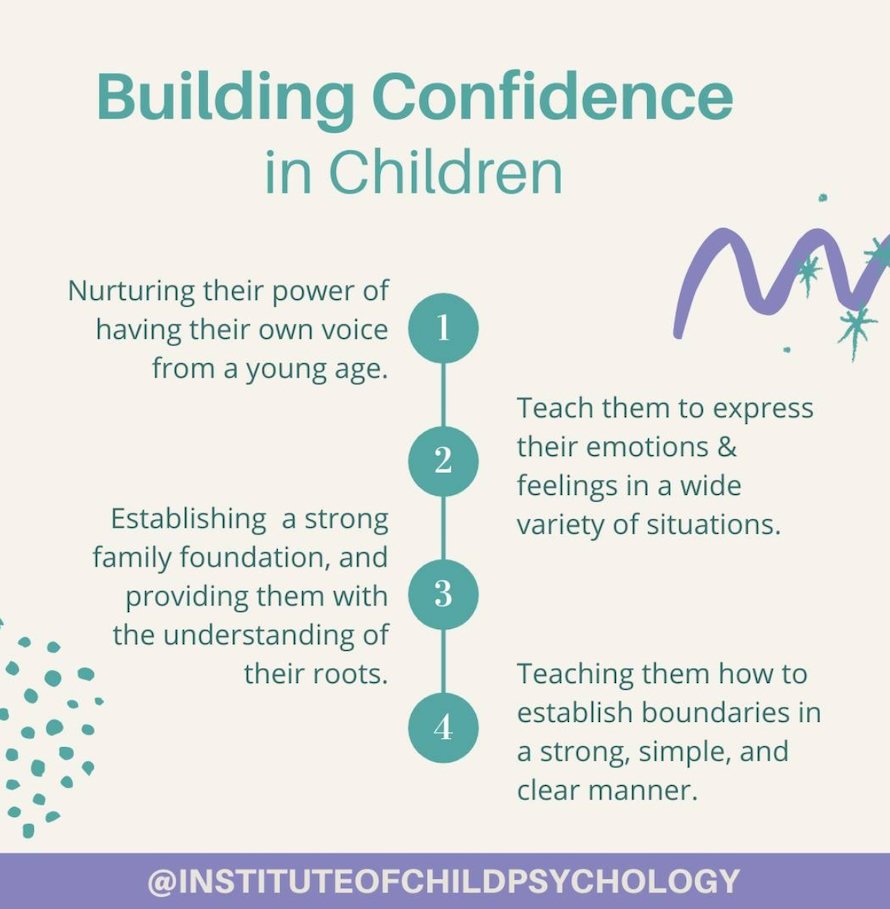

So for every blood-related parent, and every non-blood related parent, these are the rules. They just are. And they won’t be followed to the letter. But we can try. These kids we steward are not here as little stand-ins for best friends, or talismans of our perfectly put-together lives. They are people who need skills and tools to become adults who can function and thrive, with powerful inner-voices they trust, and who see the world as a collection of choices, all of which they have access to.

We all say there’s no rulebook for parenting.

What if there is?

Audie Metcalf is the Editor-in-chief of The Candidly, and lives in LA with her family. You can find more of her articles here.