Should We Still Be Blaming Our Parents Now That We’re 40?

by Carolyn Firestone

Anytime you pose a question involving “blame” and “parents,” it attracts a swarm of strong opinions. And why shouldn’t it?

It’s a subject that should come with a deep breath disclaimer - a doorway into a space inherently flooded with feeling. And based on whatever attachment pattern you grew up with, you may be more or less inclined to go through that door at all.

So before we get into too heated a discussion, we should probably break down what we even mean by blaming our parents.

First, we’re using the word “blame” to basically describe the degree to which it’s useful to make sense of and assign meaning to our parents’ ongoing impact on us.

Second, the word “parents” really refers to two things here:

The actual, influential, and imperfect people who raised us.

The influence itself - the parents we’ve internalized so to speak. These are the figures whose voices linger in our heads, whose opinions we echo (or argue against) for eternity, and whose deeply embedded prescriptions we carry on filling throughout our adult lives.

The reason it’s so crucial to separate these things is that it distinguishes our goals for ourself as adults.

“In my practice, I find that many adults are trying to resolve issues with their parents from the past so they can have a good relationship with them today,” said therapist and author Whitney Goodman, LMFT. “They are also working on patterns they inherited from their parents and don’t want to repeat as adults.”

In either case, the work you’re doing is largely internal and more about making sense of your own story than outwardly blaming anyone else.

Why dig up the past?

Attachment research shows that it isn’t necessarily what happened to us as kids that determines how we parent our own children. Rather, it’s the degree to which we’ve made sense of and felt the full pain of our experience. Simplistic as it might sound, the fact is that facing our past is key to shaping our future. And this is true of all aspects of our lives and relationships, regardless of whether we have children.

“It always makes sense to gain deeper level of understanding of our childhood experiences, because those insights give us guidance for handling our emotions in adulthood,” said psychologist and author Dr. Alfiee Breland-Noble. “For many people, the feeling of reverting to childhood can be associated with feeling obligated to parents and/or feeling a lack of control or strong sense of self in their own lives.”

When our experiences go unresolved, they tend to influence us in all kinds of silent, sometimes destructive ways, from feeling trapped by our partner to acting irritably with our kids.

When it comes to the lingering wounds our parents left us with, the answer is neither to ignore our emotions nor to get completely lost in them:

Instead, here are 6 adaptive ways to separate from our parents’ influence:

1. Acknowledge how our childhood experience with our parents is different from our adult experience.

Although as adults, we’re in control of our lives, it’s important to fully recognize and acknowledge the complete powerlessness we felt as kids.

“The word blame definitely makes sense when we’re talking about stages in the child’s life where they had no ability to care for or protect themselves,” said Whitman. “This word also fits in situations where there was abuse or neglect.” Children are, of course, also “heavily impacted by how their parents help them manage and understand the world around them,” said Whitman.

As adults, a parent “still being our parent” doesn’t give them the right to try to control, manipulate, intrude, or abuse us. But even when our current relationship with them is positive or improved, it’s important to accept that there can still be pain around everything that happened when we were little and living at their whim.

Acknowledging this pain isn’t an act of self-pity or an attack on the people our parents are today. It’s allowing ourselves to feel something that’s real and existent inside us. And it’s a significant step toward helping ourselves separate our past from our present, so it doesn’t subconsciously creep in and guide our lives.

2. Recognize our parents as people.

“It is equally important to make sense of who your parents are as human beings, separate and distinct from being your parents as it is important to understand how you were treated in childhood to inform how you engage with others,” said Dr. Alfiee.

In other words, we can accept our parents as separate people with their own struggles and shortcomings and feel whatever assortment of feelings we have toward them as separate people.

This may help us to not feel so enmeshed with our parents, as if we’re an extension of them or destined to repeat their patterns. It can also help us feel less flooded or triggered in contemporary interactions with them.

3. Keep striving for differentiation.

According to Dr. Alfiee, the process of differentiating from our parents begins in early adolescence when “a young person gains lived experiences, which then informs and reinforces their ability to be autonomous and to experience the consequences of making their own decisions without help from the adults in their lives.”

But this process doesn’t end the minute we reach adulthood. Rather, we have to keep peeling away our own point of view from the filter of our past. Sometimes, this will involve creating contemporary boundaries with our actual parents, but most often it will mean continuing to notice those unconscious overlays on our personality, particularly the voice in our heads coaching and critiquing us.

According to Dr. Goodman, differentiation is an ongoing goal in which we work to become “a unique individual with interests, preferences, opinions, and boundaries.” This can mean consciously accepting (even embracing) the positive aspects of our parents but also recognizing and releasing ourselves from the negative.

4. Control your own behavior and boundaries.

No matter what, we are not the powerless children we once were. Our early experiences and attachment patterns have created an alarm system inside us that’s programmed to go off when we get triggered. If we were ignored when we cried, our own toddler’s crying can cause us similar distress. If we took care of everyone in our family, we may get flooded with guilt anytime we do things for ourselves. And we may get thrown back into the rage of the misunderstood adolescent we once were any time our parent gets a certain judgey tone with us - even when that parent now lives 1,000 miles away.

Yet, how we react to these alarms is entirely in our control. The patterns we’ve internalized aren’t set for life. The minute we start to question and identify them as byproducts of our history and not our “role,” our nature, or our destiny, the more we can choose different actions for ourselves today. And we can create boundaries that work for us right now.

5. Don’t pressure yourself to forgive.

“You do not have to forgive your parents, especially if nothing has changed and they have not recognized their behavior,” said Goodman. “Each person has to decide what they are willing to tolerate.”

Guilt can play a very tricky role in keeping us in situations where we’re still getting hurt. It’s okay to be angry and to decide what’s healthy for us as adults.

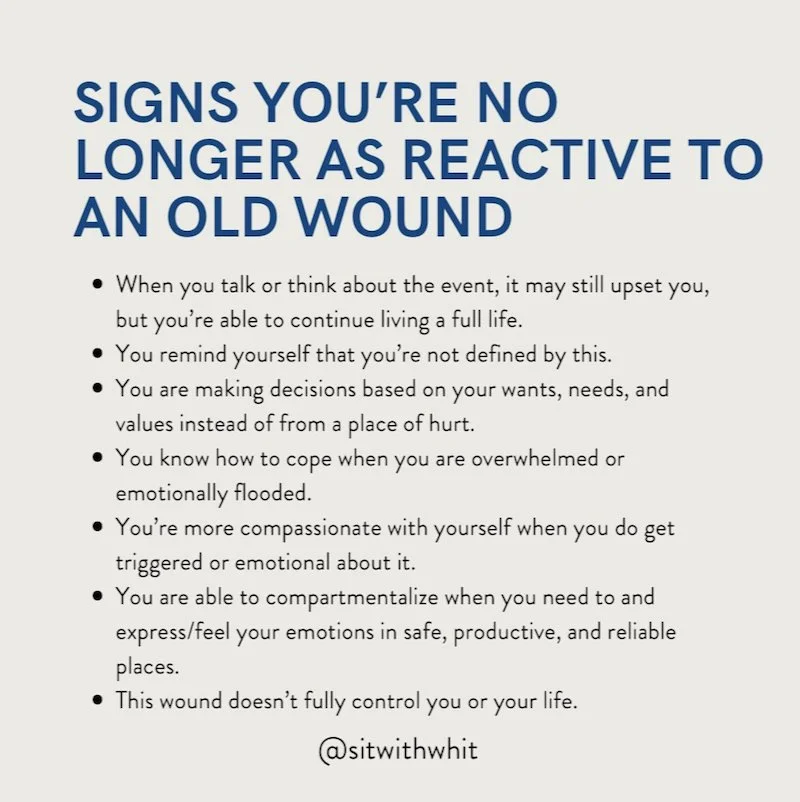

However, if we find ourselves ruminating, persistently feeling triggered, getting stuck in our pain, or still feeling like the child in a scary situation even now as an adult, it can be a sign there’s more work to be done around resolving our story. Seeking help from a therapist can be deeply beneficial in these cases (as it can be in pretty much all cases).

6. Stay curious and open about how your parents affect you.

As adults, we can work on cultivating a non-judgmental curiosity about the ways our parents affect our emotions and behavior. The key is to be open without hating ourselves for “sounding just like our mother” or “wanting to retreat into the inward tendencies of our father.” Just be willing to stay curious.

“My biggest piece of advice is the development of self-awareness,” said Dr. Alfiee. “I don’t know that we can fully avoid all suffering, but if suffering is a part of a childhood experience with a parent, then engaging in our own personal growth and development can help us identify patterns that we do not want to replicate, can help us heal from intergenerational trauma, and can help us find a way to create the type of relationship with a parent [that’s] grounded in healthy boundaries and grounded in the reality of who our parents are.”

carolyn firestone

Carolyn is a freelance writer and editor. Her favorite thing to do is to write about her favorite things, especially when they have even the slightest chance of making someone else’s something (mood, relationship, travel plans, or toiletry kit) a little better. You can find more of her articles here.

This article is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to be used in place of professional advice, medical treatment, or professional care in any way. This article is not intended to be and should not be a substitute for professional care, advice or treatment. Please consult with your physician or healthcare provider before changing any health regimen. This article is not intended to diagnose, treat, or prevent disease of any kind. Read our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.